(“Do you know what a hit man does?” Milo asks her. After bristling at her captor’s disdain for unworldly modern ahhhtists (he prefers Charlie Parker and Hieronymus Bosch), Anne decides that she actually loves this soulful lunkhead, and they should team up to kill dozens of pursuing mobsters. Even the 116-minute director’s cut, which restores some of the exposition and transitions Vestron gouged away, never maintains the same tone for longer than five minutes.

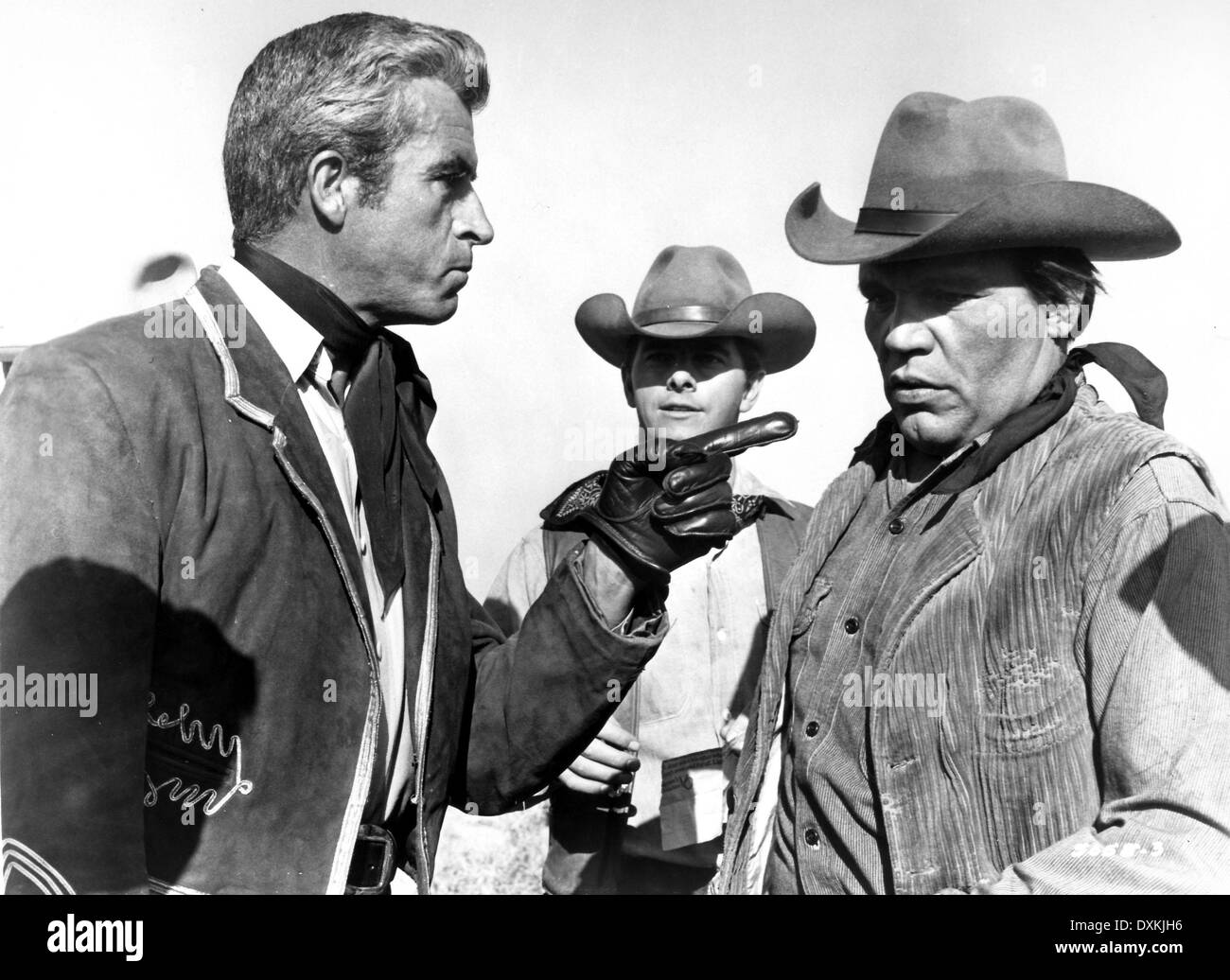

Characters slide in and out of the narrative. Entire scenes you’d expect to build up tension instead dissipate into longueurs. That might account for the sheer disjointed strangeness of the thing. Backtrack wouldn’t be dumped into theatres until 1990, sans Neil Young, under the title Catchfire. This is directed by some idiots at Vestron.” By then the distributor was already going bankrupt, and desperately hoped the movie might earn enough to pay for other moribund releases. Then they took all my music out and threw it away … They put in great violin love themes beside Jodie and me-this is a hit man and an artist, and it’s certainly not a violin romance.” The furious director demanded an Alan Smithee credit: “This is not a film by Dennis Hopper. In 1991, he told the British music magazine Vox what happened next: “They had taken an hour out of my movie, and they’d taken a half-hour of stuff I’d taken out of the movie and put it in. The initial cut Hopper presented to Vestron Pictures was two hours long. “Our forms aren’t exactly simpatico,” he says of Foster’s Anne Benton. Bob Dylan briefly cameos as a chainsaw-wielding sculptor based on Laddie Dill. Long-time collaborator Julie Adams plays a gallery owner John Turturro a gawky, giggly henchman with impractical red loafers and Neil Young is in there somewhere, giving his best ex- mafioso. Filming Backtrack that same year, he returned to the habit of casting whichever friends might be passing through. Producers tentatively started trusting him with money again: 1988’s Colors, one of the first movies to anticipate gangsta rap, was a moderate financial success. After overcoming his abyssal dependency on booze and drugs, he got an Oscar nomination for playing the saintly drunk in Hoosiers, though Blue Velvet’s terrifying one was the role that guaranteed steady villain work. Hopper shot Backtrack during an apparent resurgence.

It leapt out at me from a Wikipedia vortex one day: A Dennis Hopper crime thriller where the jazz-loving hit man Milo, also Dennis Hopper, decides to kidnap his target instead of killing her? And this conceptual artist/murder witness is played by Jodie Foster? And the wall-mounted aphorisms (“ MURDER HAS ITS SEXUAL SIDE”) he studies to track her down were all created by Jenny Holzer, beloved actual conceptual artist? Did I mention the helicopter chase? The filmmakers meant to revisit Out of the Past and, to their chagrin, succeeded. John Waters once called Joseph Losey’s Boom!“the greatest failed art film ever made.” I won’t dispute the superlative this is, after all, a movie featuring Richard Burton in a samurai outfit, Noel Coward as “the Witch of Capri,” and Liz Taylor reciting simmered-mimosa Tennessee Williams dialogue such as “he was wildly beautiful, and beautifully wild.” Backtrack is a less-mythic disaster, the wreckage of a mercurial creator smashing into capitalist imperatives, so terminally modern that the director tried to erase his own authorship-the greatest failed video installation, maybe.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)